16 Potential Solutions & the Way Forward

If you’ve made it this far having read all the previous chapters, I hope you are not dismayed at the state of research transparency and reproducibility (RT2) in science. If you are, I don’t blame you. It’s easy to feel helpless at the state of research. However, there are many advances that have been made, and that will be made to improve things. Consider this, about 15 years ago, RT2 was not really a thing. Most folks had no idea about problems with replicating and reproducing results of empirical studies. Sure, some folks like John Ioannidis were already sounding the alarms for a while as we say in Section 14.2, but I think it’s safe to say most researchers either didn’t know or didn’t care about RT2 problems (many still don’t).

Since that time, there have been a number of changes to the RT2 landscape, and a push toward Open Science has been increasing. Let’s review some of the potential solutions to the problems we’ve seen.

16.1 A Partial List

First, let’s look at a table of potential solutions advanced in an excellent Nature article entitled A manifesto for reproducible science1 in Table 16.1.

| Potential Solution Area | Example(s) of Potential Solutions |

|---|---|

| Protecting against cognitive biases | Blinding |

| Improved methodological training | Rigorous training in statistics and research methods for future researchers. Rigorous continuing education in statistics and methods for current researchers. |

| Independent methodological support | Involvement of methodologists in research. Independent oversight. |

| Collaboration and team science | Multi-site studies/distributed data collection. Team-science consortia. |

| Promoting study pre-registration | Registered Reports. Open Science Framework use. |

| Improving the quality of reporting | Using reporting checklists. Protocol checklists. |

| Protecting against conflicts of interest | Disclosure of conflicts of interest. Exclusion/containment of financial and non-financial conflicts of interest. |

| Encouraging transparency and open science | Open data, code, and related materials. Pre-registration. |

| Diversifying peer review | Preprints. Pre- and post-publication peer review such as Publons and PubMed Commons. |

| Rewarding open and reproducible practices | Badges. Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines. Funding replication studies. Registered Reports. Open science practices in hiring and promotion. |

That’s a pretty good list. It’s not complete, nor could it be, as advances are continually being made, but it’s summarizes potential solutions across a number of areas nicely. Let’s now explore some potential solutions in detail.

16.2 Pre-registration

16.2.1 General Description

Pre-registration refers to specifying your research plan in advance of your study and submitting it to a registry.2 It’s basically saying what you plan to do and how you plan to do it, and then publishing those details in the public domain before you conduct your study. In this way, pre-registration separates hypothesis-testing (confirmatory) research from hypothesis-generating (exploratory) research as shown in Figure 16.1.

As we saw in Chapter 15, humans are prone to several cognitive biases which can affect our ability to separate a priori from a posteriori thinking, even if we do not mean to conflate the two. Pre-registration can mitigate these biases by clearly stating at the outset what analyses will be used to confirm or falsify hypotheses, and which analyses will be exploratory. Then, the reader can judge the merit of the work for themselves. Ideally before a researcher collects any data, they should pre-register their confirmatory hypotheses and related analyses in the public domain. There are several benefits of doing so in terms of reducing bias due to:

- Selective reporting of outcomes.

- Different analytic decisions that can lead to different results.

- Publication bias, because it corrects the denominator of studies and hypotheses out there.

- Cognitive biases like apophenia, hindsight bias, and confirmation bias.

16.2.2 Common Apprehensions

Now, let’s say you followed my advice above and pre-registered your study in the public domain prior to data collection. Then, in the course of the research process, you discover that something you said you would do in your pre-registration isn’t working, and you have to pivot to a different strategy. Is that OK? Yes! As long as you clearly state any deviations from your pre-registered plan, it’s totally fine if you need to adjust something. It’s all about being transparent about what you did. Additionally, even if you already have a dataframe you want to analyze, you can still pre-register your analysis plan prior to analyzing the data. This is not the ideal scenario as it still leaves a researcher degree of freedom to cheat and peek at the data, but at least it shows people exactly what you did and readers can judge the veracity of the pre-registration for themselves.

You may wonder, Won’t someone steal my ideas if I pre-register my ideas? This is a valid concern, and though I don’t believe this happens frequently, the point is that it can happen. The solution is therefore to embargo the pre-registration, which keeps it private for a certain amount of time (up to four years on some platforms) before it is made public. This allows researchers plenty of time to conduct a pre-registered study without worrying about their ideas being stolen (also known as getting scooped). Additionally, once the researcher’s ideas are pre-registered and public, that provides a timestamp to lay claim to their ideas. That is, if someone else steals your exact set of analyses, data, and code, you have a record of having registered these in the public domain prior to their study being published. In my experience, getting your ideas stolen due to preregistration doesn’t really happen. In fact, some believe that the fear of being scooped is not a legitimate drawback against pre-registration as papers are unlikely to be rejected due to scooping alone, no two scooped studies can be the same, and if someone uses your methods on a different sample, that’s actually a good thing for science!3 Of course, if one is still afraid, the embargo period is an elegant solution.

16.2.3 What Should Be Included & Where to Pre-register

You can be as detailed as you want in a pre-registration, but there are a few elements that should be described as a minimum. For instance, you should describe the hypotheses, planned analyses, and criteria for falsifying or supporting the hypotheses. In general, a reader should be able to replicate the methodology used, and the pre-registration should minimize as many researcher degrees of freedom as possible for confirmatory analyses. Personally, I treat the pre-registration as the bulk of my Methods section that will eventually end up in the published manuscript (save any deviations from the pre-registration which I include later in the final manuscript). This includes information about the variables being measured, a detailed analysis plan, and several back-up plans if what I want to do fails for some reason. If possible, the actual code that will be used to conduct the analyses should be included as well.

The pre-registration platform aspredicted.org provides perhaps the simplest template for create a pre-registration, wherein researchers need to answer the following eight questions:

Have any data been collected for this study already?

What’s the main question being asked or hypothesis being tested in this study?

Describe the key dependent variable(s) specifying how they will be measured.

How many and which conditions will participants be assigned to?

Specify exactly which analyses you will conduct to examine the main question/hypothesis.

Any secondary analyses?

How many observations will be collected or what will determine sample size?

Anything else you would like to pre-register (e.g., data exclusions, variables collected for exploratory purposes, unusual analyses planned)?

My favorite platform for pre-registration and posting all research materials in the public domain is the Open Science Framework (OSF).You can pre-register any study on the OSF, and it’s a great place to also put all your de-identified data, code, and materials used to generate your analyses. Besides having an excellent repository of study materials and pre-registrations, the site also provides several resources for learning more about pre-registration and Open Science. It also has an embargo period of four years should you wish to maintain privacy of the pre-registration for a certain period of time.

There are also study design-specific registries. For instance, the American Economic Association has a registry for Randomized Controlled Trials only. The PROSPERO registry hosted by York University in the UK is THE go-to place to register systematic reviews, meta-analyses, rapid reviews, and umbrella reviews. Clinical trials in the US have to registered on clinicaltrials.gov, but this registry is also applicable to any social science randomized controlled trial. The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) hosts the Registry for International Development Impact Evaluations. Thus, there are many places to pre-register a study! If you’re at a loss for where to register, I suggest trying the Open Science Framework.

Want to see an example of a real study pre-registration? Here’s one of mine on the Open Science Framework. It’s got hypotheses, analysis plans, diagrams, equations, references, and all kinds of good stuff! This study analyzed restricted-access longitudinal secondary data. This meant that I had to apply to get this data from a data vendor. Only after receiving the data could I gauge what variables I could include in an analysis plan. As a result, I create two pre-registrations: one before I received the data, and another after receiving the data but before conducting my main analyses. The link is to the second pre-registration, but you can also find a link to the first pre-registration on the same page. Check it out!

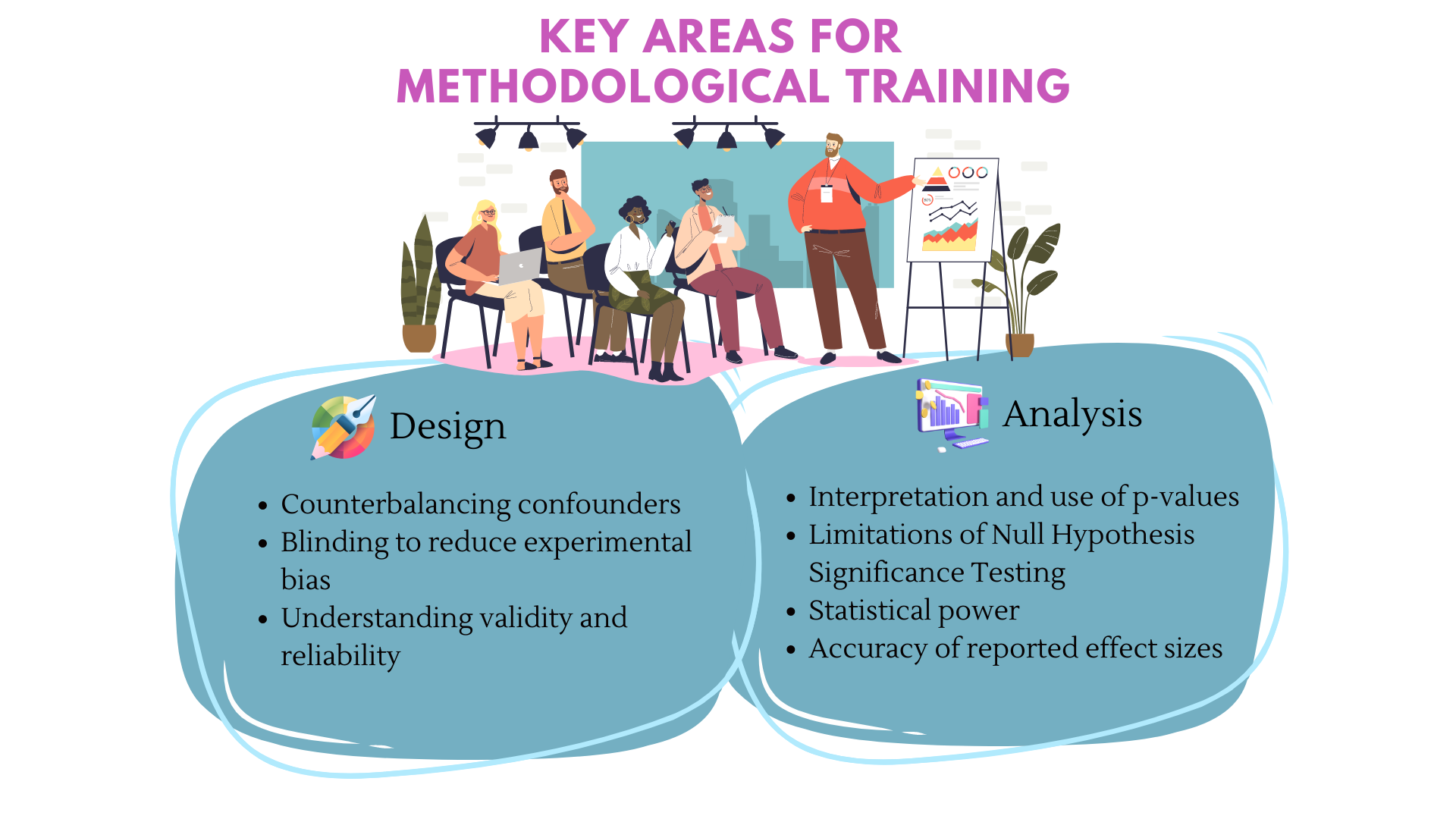

16.3 Improved Methodological Training

Any scientific discipline that makes use of statistical analysis can be open to researcher degrees of freedom, and consequently, spurious research findings. Thus, appropriate and rigorous statistical training is needed for robust quantitative science. Additionally, researchers need robust training in study design and implementation. Research design and statistical analyses are mutually dependent and reinforcing.1 Even if you’ve received a PhD with solid training in statistics, keeping up the latest advances requires a concerted effort, and is necessary. In particular the following areas of methodological training have been cited as especially crucial to RT2,1 seen in Figure 16.2.

The use of statistics in quantitative research is so ubiquitous that you’d be hard-pressed to find a scientific field that DOES NOT use statistics for any research involving numbers. Thus, most researchers may not be specialists in statistics (I know I’m certainly not), but need to know they key components in order to use them appropriately. This is why it is crucial to consult methodologists (those whose primary work concerns methodology development and training) and statistical experts whenever possible. However, non-specialists who use statistics should be appropriately trained so we don’t make the same mistakes as researchers in the past. When reporting the results of a study, some suggest a simple 21-word ‘solution’:

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study.”4

This isn’t a ‘solution’ in the mathematical sense or in the sense we are discussing here. Rather, it’s a sentence that prompts researchers to clearly describe important elements of their study.

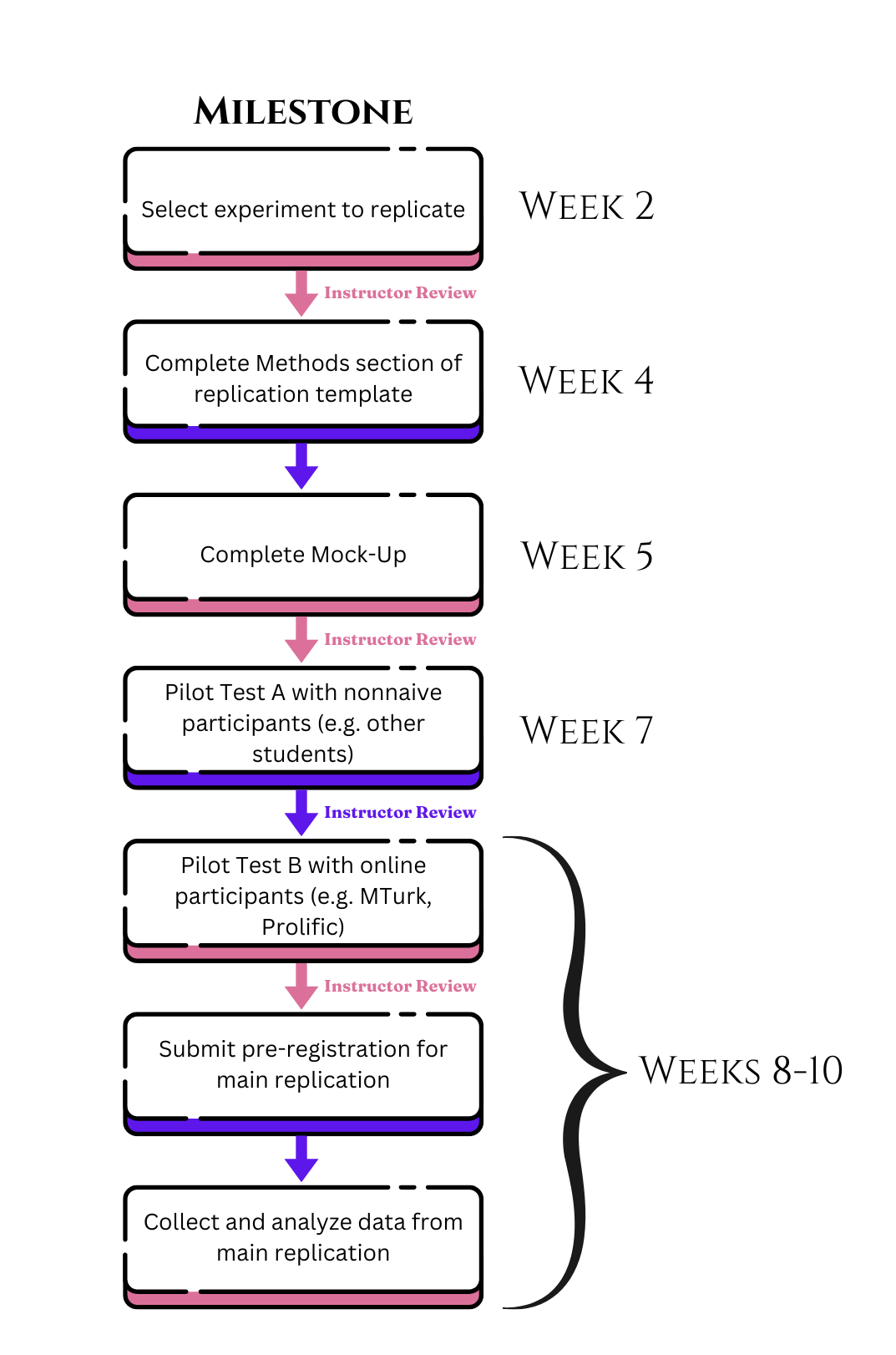

One useful way to improve methodological training is to train students to replicate a given study. This can apply to students in formal degree programs, but could just as well be applied to participants at a workshop who may be continuing their education. This is commonly done in certain fields currently, but there’s no reason why it cannot be applied broadly to any fields who engage in quantitative research. In fact, there is an increasing push toward teaching replication at the undergraduate and graduate levels.5 67 An example of a replication pedagogy workflow for a graduate-level experimental methods courses is shown in Figure 16.3.

The schematic above illustrates one possible pedagogical workflow for a graduate-level course over 10 weeks. It’s not the only approach, but a good place to start. In this workflow, students begin with writing brief proposals for determining which studies they want to replicate, which are reviewed by an instructor for feasibility. Next, they complete the Methods section of a replication template developed by the Open Science Collaboration.8 They then work on outlining their proposed replication experiment, which is reviewed by the instructor. Once approved, students proceed with their experimental protocol in two pilot tests. The first test is conducted with nonnaive participants, meaning the people in the class. This is to make sure the data are logged accurately, and confirmatory analysis code is working properly. After an instructor reviews the results, students proceed to a pilot test with real-world participants who are not in the class on an online platform such as MTurk or Prolific. This is done to make sure participants don’t experience any issues with completing the experiment, and to solicit feedback to determine if any design changes should be made. Following instructor review of the second pilot test, students pre-register and run their main replication.

By making replication and pre-registration familiar to students, the hope is that this will transfer into actual research practice. At the very least, it can help normalize these processes by including them within curricula.

16.4 Incentives

How does one incentivize Open Science practices like sharing data, code, and related materials in the public domain? One promising approach is inspired by the world of video games! Really! If you’ve ever played a video in the past 10 years or so, you have likely encountered some variation of an achievement badge for some task (e.g., leveling-up, defeating a boss, etc). The Center for Open Science developed several digital badges for use by journals to award researchers for pre-registering their study, sharing their data, and sharing their materials. The current suite of badges are shown in Figure 16.4.

Over 100 journals currently award these open science badges to authors who do the thing associated with each badge. The meaning of each badge is summarized in Table 16.2.

| Badge | Description |

|---|---|

| Preregistered | At least one study has been preregistered with descriptions of the research design and study materials, including the planned sample size, research question(s) or hypothesis(ses), outcome variable(s), predictor variable(s). Results must be fully disclosed. |

| Preregistered✚ | At lease one study has been preregistered along with the analysis plan for the research, and the results are reported according to that plan. |

| Open Materials | All digitally-shareable materials necessary to reproduce the reported results are provided, and description of non-digitally-shareable materials needed for replication are made publicly available. |

| Open Data | All data needed to reproduce results are made publicly available. Necessary metadata or codebooks are also provided. A list of such repositories is available here. |

| Open Data (PA) | PA stands for Protected Access. This refers to data that are sensitive or only available from an approved third-party repository that manages access to the data only for qualified researchers. |

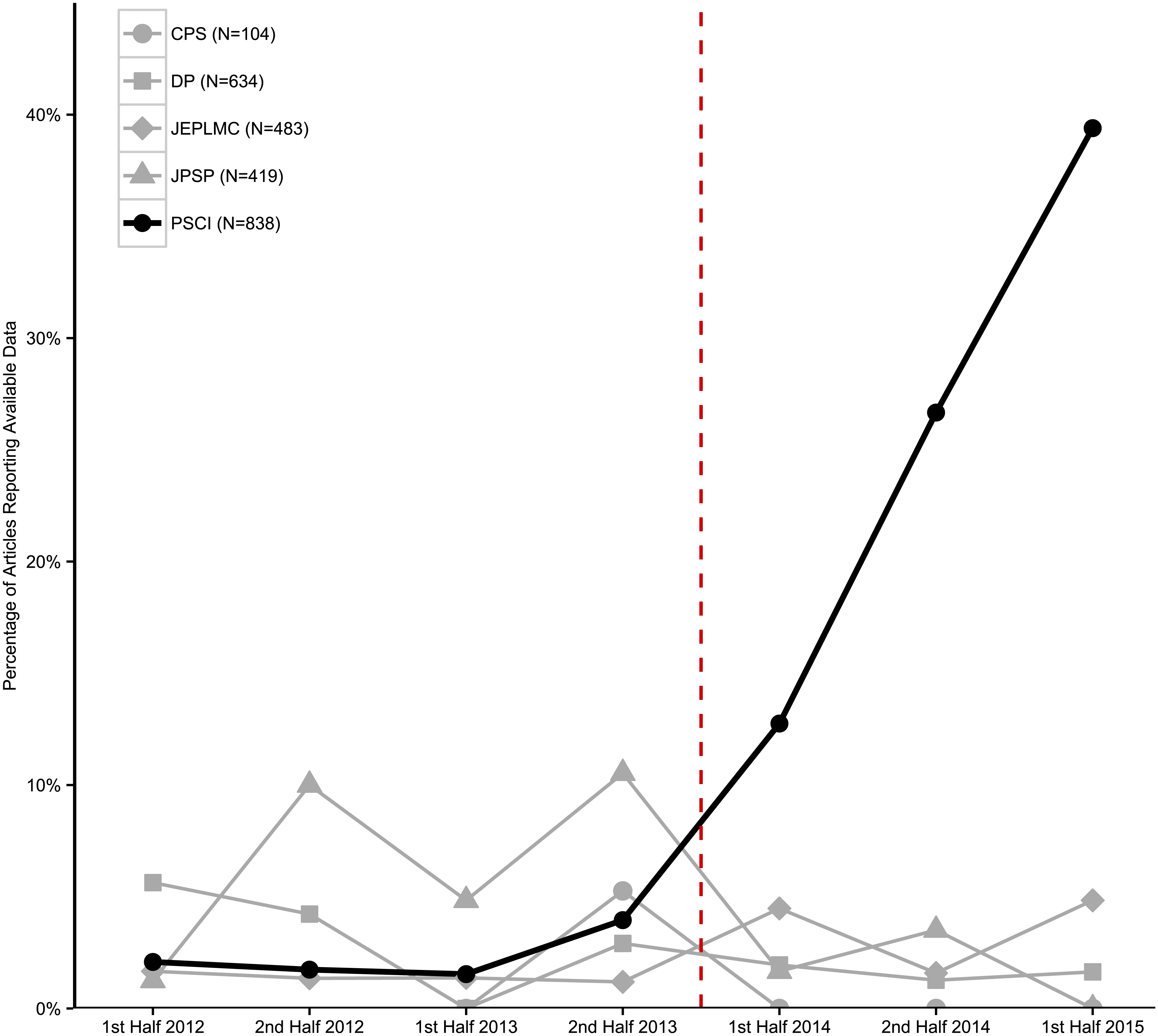

While the badges might seem silly, they can actually make a difference to Open Science practices. To see if the badges encouraged data sharing, a group of researchers examined 2,478 experimental or observational study articles published from 2012 to the first half of 2015 in five psychology journals.11 One of these journals Psychological Science began awarding open science badges in late 2013. The other four journals were all respected journals in psychology that did not award open science badges during the 2012 to 2015 study period. The results are quite telling. Check out their findings related to the effect of badges on data sharing in Figure 16.5.

The findings suggest that the badges increased data sharing, as well as the usability and accuracy of the data shared. The rate of data-sharing in Psychological Science increased from 1.5% to 39%, while the other journals stayed at 5% or less. However, badges are still not going to create more open practices on their own. An evaluation of badge use by the British Medical Journal for instance found that the badges did little to increase data sharing.12 A similar evaluation of badge use by the journal Biostatistics showed an increase in data sharing due to badges, but of only about 7.6%, with no impact on code-sharing.13 Thus, badges alone will not solve the problems in the field, but they are a simple, low- (or no) cost incentive that can improve things, even if only a little bit.

16.5 Funders Hold Tremendous Power

Perhaps better than an incentives for researchers to engage in Open Science practices are requirement to do by funders. For instance, cOAlition S is an initiative by various international organizations and funders to make all research funded by national, regional or international research councils and funding bodies made available immediately in Open Access repositories and journals. This took effect from 2021 and continues to this day among funders who subscribe to this organization’s Plan S Principles presented below.14

Authors or their institutions retain copyright to their publications. All publications must be published under an open license, preferably the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY), in order to fulfil the requirements defined by the Berlin Declaration.

The Funders will develop robust criteria and requirements for the services that high-quality Open Access journals, Open Access platforms, and Open Access repositories must provide.

In cases where high-quality Open Access journals or platforms do not yet exist, the Funders will, in a coordinated way, provide incentives to establish and support them when appropriate; support will also be provided for Open Access infrastructures where necessary.

Where applicable, Open Access publication fees are covered by the Funders or research institutions, not by individual researchers; it is acknowledged that all researchers should be able to publish their work Open Access.

The Funders support the diversity of business models for Open Access journals and platforms. When Open Access publication fees are applied, they must be commensurate with the publication services delivered and the structure of such fees must be transparent to inform the market and facilitate the potential standardisation and capping of payments of fees.

The Funders encourage governments, universities, research organisations, libraries, academies, and learned societies to align their strategies, policies, and practices, notably to ensure transparency.

The above principles shall apply to all types of scholarly publications, but it is understood that the timeline to achieve Open Access for monographs and book chapters will be longer and requires a separate and due process.

The Funders do not support the ‘hybrid’ model of publishing. However, as a transitional pathway towards full Open Access within a clearly defined timeframe, and only as part of transformative arrangements. Funders may contribute to financially supporting such arrangements.

The Funders will monitor compliance and sanction non-compliant beneficiaries/grantees.

The Funders commit that when assessing research outputs during funding decisions they will value the intrinsic merit of the work and not consider the publication channel, its impact factor (or other journal metrics), or the publisher.

Many international funders have already endorsed the Plan S Principles such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Health Organization, Templeton World, the Wellcome Fund, and others. Additionally, a number of journals have also begun adopting the Plan S Principles. Specifically, a Transformative Journal is one that is committed to transitioning to a fully Open Access journal (one that does not place access restrictions on its articles).14 These are small steps, but when funders require Open Science practices, that can be a powerful force for change.

16.6 Reporting Guidelines

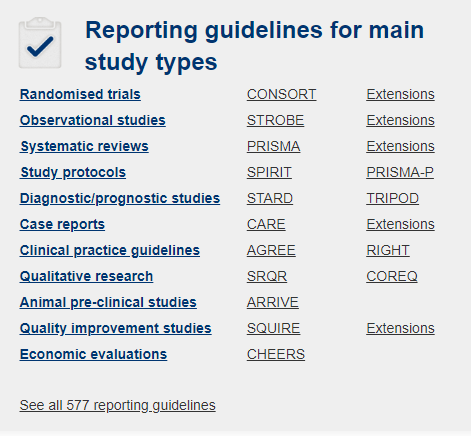

Reporting guidelines are simple tools that provide a minimum list of information that should be included when writing a study. Having a common minimum set of guidelines helps create consistency across the field, and improve the quality of reporting. For instance, the Equator network is an organization that brings together researchers, funders, journal editors, and others in service of improving the quality of published research. They have links to 577 different reporting guidelines across diverse study designs, research areas, and fields. Some of the main guidelines that researchers use are listed in Figure 16.6. The use of such guidelines is often required by particular journals, and can be a great way to obtain relevant information about key aspects of a study.

In fact, we now even have Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) guidelines which specify eight standard toward greater scientific openness.15 The complete list of guidelines can be found here. There are now thousands of journals that have implemented at least two of the TOP guidelines, and journals can be checked for their TOP Factor which provides a numeric rating of how well they are implementing Open Science practices. The directory of journal TOP factors can be found here.

16.7 Preprints and Registered Reports

Preprints are research papers that are shared in the public domain prior to peer review. They typically have a digital object identifier, so they can be cited. The benefits of doing so are typically to receive credit for one’s ideas and findings without waiting for the often-long peer review process to conclude, to receive feedback from other experts in the field, and to increase visibility of one’s research.16 They can also be a great place to deposit null results that may not be accepted by journals due to publication bias. In this way, they can correct the denominator of studies and hypotheses on a topic, which can be particularly useful for evidence syntheses. There are several places to publish preprints, and an entire director of preprint servers is available here. Some examples of preprint servers include SSRN, ArXiv (pronounced ‘archive’), Preprints.org, medRXiv, and many more.

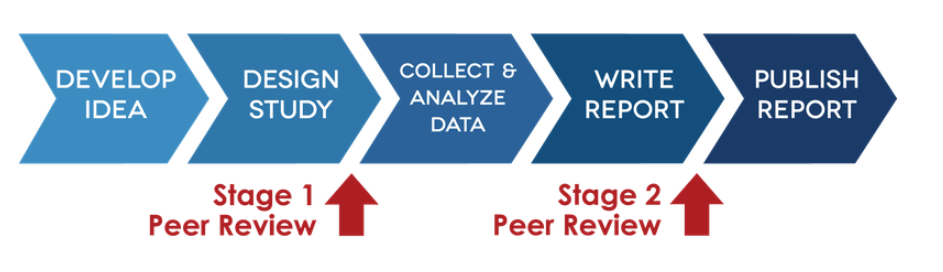

Registered reports are a relatively newer publishing format that involve two stages of peer review: one on the methodology of the planned study before data are collection, and another after the data are collected. The idea is to eliminate publication bias by agreeing to publish work that is methodologically sound, regardless of statistically significant outcomes. Journals that allow this format review the methodology and analysis plan in the first stage, and can choose to accept it, reject it, and accept it conditional on revisions. If it accepted, then the journal grants in-principle acceptance to the authors, meaning that they will publish the study regardless of the outcome as long as the authors stick to the protocol they described. The basic workflow of a Registered Report is presented in Figure 16.7.

There are now over 200 published Registered Reports, up from just a handful in 2014.18 They are not appropriate for every type of research, such as mainly exploratory work, but can be a valuable mechanism to mitigate researcher degrees of freedom and publication bias.

16.8 Conclusion

In sum, we have a lot of work left to do to clean up the research landscape. New advances are constantly being made, and an entire field of Meta-Science (science about science) or Meta-Research (research about research) has sprung up in the last decade or so to formally study many of the issues we have seen. Far from feeling hopeless, there are plenty of reasons to be excited about a better future for RT2!