11 A Very Brief History of Replication

11.1 What is Research Transparency, Reproducibility, and Replication?

By now, you should be swimming along in understanding the preliminaries of R. Hopefully, you are practicing and ensuring you have nailed down all the basics.

While it can be tempting to continue along this road, and immediately jump to the next topic in R, this is actually a good time to slow things down, and understand what we are doing in this course. This is not a course in how to code in R, at least not entirely. This course is also about the very consequential problems and solutions involved in Research Transparency & Reproducibility (RT2). Let’s begin with some definitions of these terms from the United States National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.1

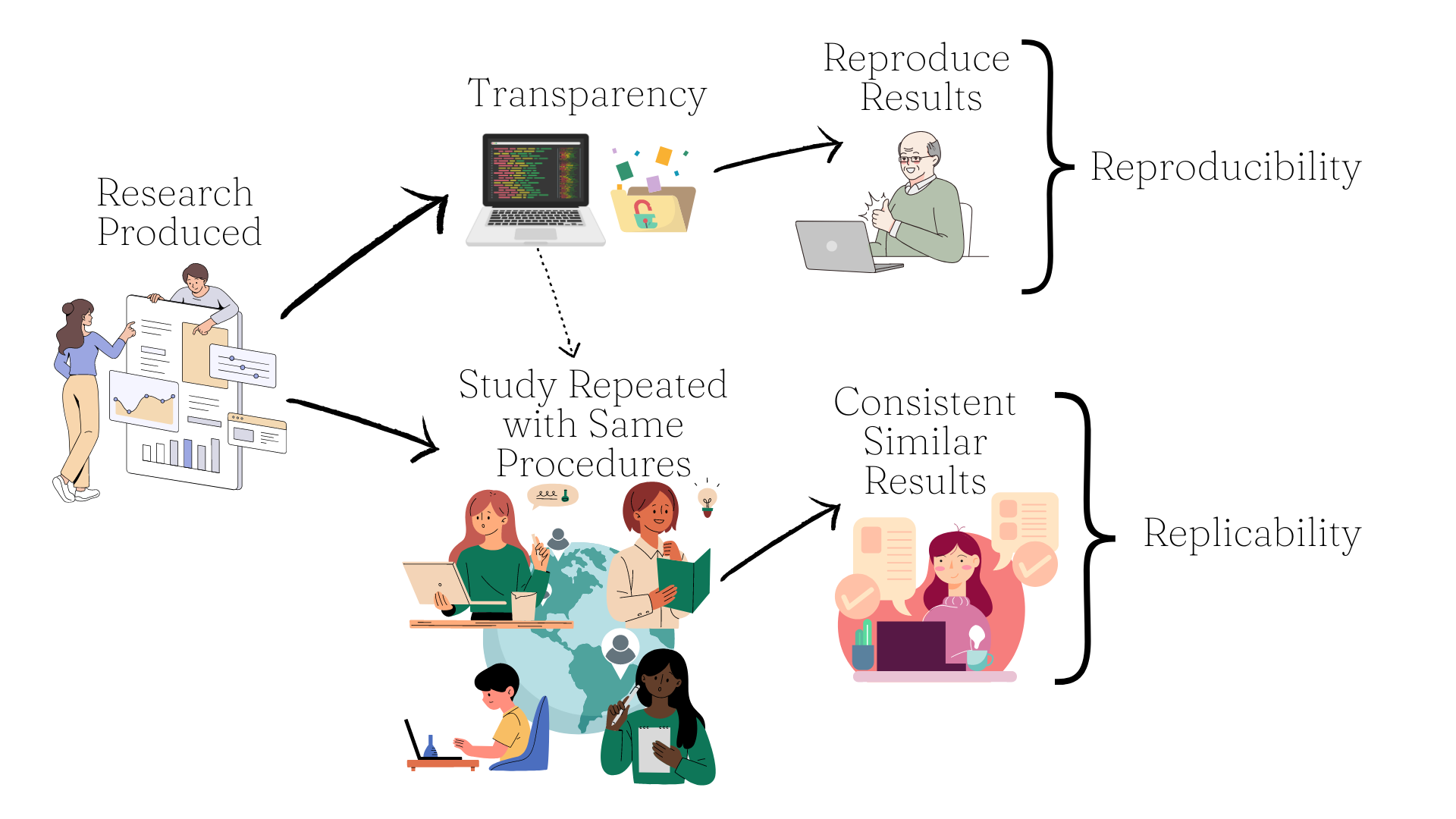

Reproducibility - Obtaining consistent computational results using the sample input data, computational steps, methods, code, and conditions of analysis.

Replicability - Obtaining consistent results across studies aimed at answering the same scientific question, each of which has obtained its own data.

Think of reproducibility as checking the results of the original study. If a researcher gave you their code and data, could you reproduce or recreate their analyses and have them match? That’s the hope anyway, but you would be surprised how often that does not happen.

Think of replication as conducting multiple studies, using the same methods and procedures as the original study. If you arrive at similar results, that’s good and shows that the underlying theory seems to hold. If not, then it could be a) a problem with the underlying theory, b) a problem with the methods or procedures, or c) both.

Finally, as stated by the National Academies, “Reproducibility is strongly associated with transparency; a study’s data and code have to be available in order for others to reproduce and confirm results.”1 Thus, transparency typically refers to availability of data, code, and materials used to produce the results of a study. However, the term conveys more than that. Another definition of research transparency is as the obligation to “make data, analysis, methods, and interpretive choices underlying their claims visible in a way that allows others to evaluation them - as a fundamental ethical obligation.”2 This extends beyond mere availability of data and code to a fundamental way of doing ethical research.

The definitions are illustrated in the Figure 11.1.

Now that we’ve got definitions for the terms, let’s have a look at some key (and in some cases oft-forgotten) players in the history of replication and reproducibility.

11.2 Replication Origins

The history of replication is closely tied to the history of the Scientific Method. Many individuals over time likely contributed to it, but let’s have a look at a few key figures throughout history. The focus here is not on the Scientific Method per se, but rather on the use of replication or repeated experimentation.

11.2.1 Ibn al Haytham

One of the earliest proponents of an approach we later would know as the Scientific Method was Ibn al-Haytham, a mathematician, astronomer, physicist, and all-around scholar who lived from 965-1040 CE. Born in Basra, modern-day Iraq, Al Haytham is known as the Father of Optics for his pioneering work on the subject in his famous work كتاب المناظر (Kitab al-Manazir or Book of Optics), which provided empirical evidence that vision occurred when light entered the eyes (intromission), rather than light being emitted by the eyes (extramission), which was argued by Euclid in Optica.

Besides his many scientific contributions, particularly to the field of Optics, al Haytham made use of repeated systematic observation of natural phenomena to argue his points. Even in his magnum opus Book of Optics, he often ends a description of an experiment with the phrase “this is always found to be so, with no variation or change”, emphasizing that repetition was a central argument of his experimental findings.3

While this may not seem that impressive to us today, consider that Al Haytham was working in his way before we had the term Scientific Method, and about 500 years before Galileo started looking through telescopes! The important takeaway from Al Haytham is that accidental conditions might distort one’s observation of a phenomenon, and we’re better off making multiple observations before making any grand claims.

11.2.2 Abu Rayhan Al Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni was a Muslim polymath who lived from 973 - 1050 CE. He was known to have authored 146 books, with the majority written on mathematics, astronomy, and related subjects. He was also one of the earliest scholars to offer a formal refutation of astrology in contradistinction to astronomy, which he considered a legitimate science based on empiricism. He made contributions to many fields such as physics, astronomy, geography, and Indology (the study of India).

Importantly, al Biruni contributed to the development of the scientific method, and was one of the first documented scientists who thought about how to separate measurement of a phenomenon from errors in the measurement device. This was remarkably foresighted, as the issue of measurement error is unavoidable in the natural and social sciences. Al Biruni noted that measurement errors can come from different sources such as measurement tools and human judgment, and can compound.4 To address the issue, he recommended taking multiple measurements of a phenomenon and then quantitatively combining them to arrive at a common-sense estimate. This is an approach we still take today with a number of applications, but especially in the use of multiple survey questions to study latent or unobserved phenomena like attitudes, emotions, and perceptions.

11.2.3 Roger Bacon

Picking up where Ibn al Haytham left off, Roger Bacon was a philosopher and Franciscan friar from England who lived from 1219 - 1292 CE. He took al Haytham’s scientific method and applied it to works by Aristotle. He was the first person in Europe to describe the formula for gunpowder (it was invented and known about in China already). Crucial for our purposes, he was an early proponent of a method of observation, hypothesis, experimentation, and the need for independent verification as noted in his Opus Tertium, published in 1267. Regarding the latter, he kept very meticulous notes about his experiments, permitting reproducibility by others. This is exactly what we try to do today!

11.2.4 Andries van Wesel

Andries van Wesel (also known as Andreas Vesalius) as a Flemish anatomist who lived from 1514-1564 CE. He is most famous for creating detailed drawings of human anatomy that provided new insights into the subject, correcting a number of errors made by the Greek physician Galen (129-216 CE), and followed by physicians for centuries.

In the summer of 1542, he published his magnum opus De humani coporis fabrica libri septem (On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books), which was based on a collection of his lectures delivered at the University of Padua, where he was a professor. Based on his own experiences dissecting corpses (not a common practice among physicians at the time), he was able to show that the Galen never dissected a human corpse because he made many errors in human anatomy.5 Galen instead had relied on dissections of animal corpses, and assumed humans had the same anatomy. Van Wesel was able to show that Galen made 300 errors in human anatomy. Finally, van Wesel was able to create detailed visualizations leveraging newer techniques of printing with woodcut engravings. This was huge, because it allowed other physicians to dissect corpses and verify what van Wesel was claiming. This is one of the earliest examples that I’ve seen of evidence-based medicine triumphing over eminence-based medicine. This meant that you didn’t have to take his word for it, you could actually dissect a corpse and check if what you saw lined up with his illustrations. This is very much in line with how we think about replication today!

Did you know that dissecting human corpses was strictly prohibited by the Catholic Church in the 16th century? Andries van Wesel had to secretly ‘steal’ the bodies of executed criminals to perform his dissections. This allowed him to correct many of Galen’s errors of anatomy. Have a look at his illustrations here.

11.2.5 Francis Bacon

Sir Francis Bacon was an English philosopher and statesman who lived from 1561 - 1626 CE. He is sometimes called the father of empiricism, but of course we know that he stood on the shoulders of giants who came before him. He put forward a method of inductive reasoning in his magnum opus Novum Organum (New Method) which stressed the importance of making systematic observations of phenomena, and then to generalize the observations to a few axioms. He also noted that it was important to have a skeptical and methodological approach, so that scientists would not mislead themselves, and to not generalize beyond what the facts demonstrate. The latter sentiment is particularly relevant today as authors of scientific papers frequently discuss broad-reaching implications of their findings, which really cannot generalize beyond their samples. In fact, some have suggested adding a “Constraints on Generality” section to the discussion section of every paper, in which authors clearly state the specific population to which their findings apply.6 I feel like Sir Francis would approve.

In addition to his many contributions to the formation of the Scientific Method, Bacon also stressed the need for repeated experimentation to create an increasingly complex knowledge base that is always supported by observable facts. This is highly in line with how we think about replication today, as we aim to support or reject theories of how things work. Finally, Bacon also listed several “idols of the mind”, which he noted as obscuring the path of correct scientific reasoning. These include the human tendency to perceive more order in a system than actually exists, confusion arising from the scientific use of certain words compared with their common usage, and the tendency to follow dogma and not ask questions about the world. These are what we would today refer to as cognitive biases, and they have an important role in inhibiting research transparency and replication, which we will discuss later.

In short, Sir Francis reaffirmed the need for repeated experimentation, careful observation, and meticulous record-keeping in the conduct of science.

While many others contributed to the refinement of the Scientific Method over the next 500 years or so, for our purposes to will skip to the 20th century.