12 Mertonian Norms and Counter-Norms

12.1 Background

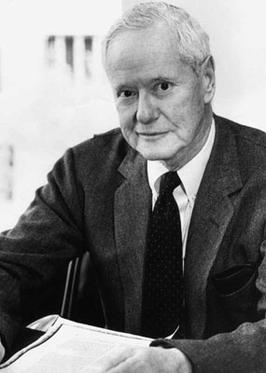

Robert K. Merton lived from 1910 - 2003 and made a number of major contributions to sociology, criminology, and the sociology of science. Unlike some of the early figures in the history of replication we saw in Chapter 11, Merton advocated for theorizing to begin with middle-range theory, or starting with aspects of a phenomenon that are clearly understood, constructed with observed data. He intended this to be a middle ground between a grand theory and a description of a phenomenon. This is remarkably contemporary, as a great deal of middle range theory is about underlying mechanisms that give rise to phenomena.1

Reflecting on the history of science, Merton noted that scientists could no longer isolate themselves from the concerns of society.2 He could have been a poet, because his descriptions of this observation are loaded with powerful imagery that summarize his position nicely. Let’s look at a few of these quotes with my crude interpretations interspersed.

| Merton’s Quote | My Crude Interpretation |

|---|---|

| A tower of ivory becomes untenable when its walls are under prolonged assault. | Hey scientists, you can only pretend society doesn’t exist for so long, until you can’t. |

| A frontal assault on the autonomy of science was required to convert this sanguine isolationism into realistic participation in the revolutionary conflict of cultures. | Hey scientists, when bombs start falling, you better get in the game! |

| Science is a deceptively inclusive word which refers to a variety of distinct though interrelated items. | Like, what even is Science? |

| The ethos of science is that affectively toned complex of values and norms which is held to be binding on the man of science. The norms are expressed in the form of prescriptions, proscriptions, preferences, and permissions. They are legitimized in terms of institutional values. | Science is done a particular way, and you can see that in a bunch of places. |

As you will note, Merton was interested in the way science was done, and with its explicit and implicit beliefs, norms, and aspirations. In short, he was interested in spelling out an ethos of science, or the character of ideal scientific inquiry. While Merton made many valuable contributions to social science, we are primarily concerned with his notion of Mertonian Norms, which are given by the acronym CUDOS.

12.2 CUDOS

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Communalism (called Communism by Merton) | Public ownership of scientific goods. |

| Universalism | Validity of findings as independent of the status of human subjects. |

| Disinterestedness | Scientific institutions act for the benefit of a common scientific enterprise, and not for personal gain. |

| Organized Skepticism | Scientific claims should undergo critical scrutiny before being accepted. |

Let’s make sure we have a good sense of each of his norms (i.e. CUDOS) before proceeding.

12.2.1 Communalism

Merton believed that science should produce goods under common ownership of the community (he called it Communism but scientists instead often call this Communalism because the former has…certain connotations unrelated to science). The idea here is that a major discovery in science in not the exclusive property of the discoverer. You might get something named after you (known as Eponymy, such as Boyle’s Law or Schrödinger’s cat), and maybe some recognition, but you don’t get to own the discovery as this contradicts the scientific ethic. Secrecy in the antithesis of this norm, and “full and open communication” is related to putting the norm into practice. Merton notes that this norm is incompatible with the definition of technology as private property.

A study investigated 36 top ranked apps for depression and smoking cessation for Android and iOS in the US and Australia in 2018.3 The study found that of the 36 apps, 29 shared user data to Google and Facebook, and only 12 of these accurately disclosed this information in a privacy policy. How does sharing findings on users with commercial entities align with the Mertonian norm of Communalism?

12.2.2 Universalism

The acceptance or rejection of particular research claims should be impersonal. It should not depend on the author’s race, gender, nationality, alma mater, or any personal characteristic. Merton believed that the impersonal character of science was deep and rooted in Universalism. He was also realistic and understood that the larger culture within which science is housed can be antagonistic to the norm of Universalism. In particular, nationalistic bias and related forces can create the situation where “the man of science may be converted into a man of way - and act accordingly.”2 Knowledge cannot be advanced and furthered if scientific careers are restricted on grounds other than competence, according to Merton. It shouldn’t matter who you are as long your work is competent and adheres to the standard of quality in a field. Unfortunately, implicit and explicit can creep in during process of hiring researchers, the peer review process, and the consumption of research. This is why many journals operate using a double-blind process, whereby neither the authors nor the reviewers know the identity of the other.

When I was an undergraduate research assistant at the University of Michigan in the US, I once brought a paper to the attention of my supervisor, who was a young PhD student educated in the US. When they asked what journal the paper came from, I replied “the Indian Journal of Psychology.” Without looking at the paper, they said “Hmm, see if you can find a paper from a better journal.” I dutifully went looking for another paper, but not before reflecting “Why didn’t they look at the study before making a decision on its quality?” As an Indian studying in the US, this experience illustrated the mental shortcuts frequently made in academia, illustrating a stark deviation from the norm of Universalism.

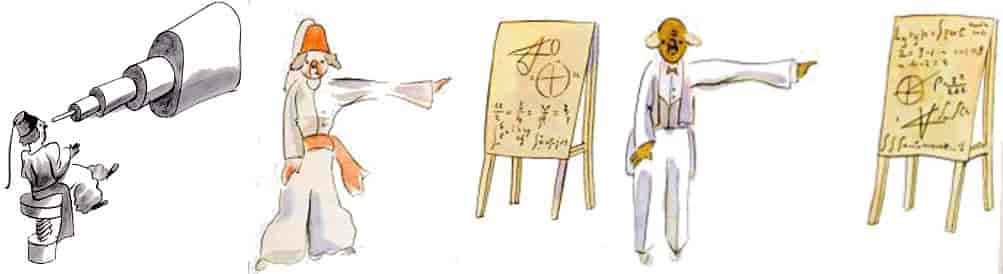

When I first read about the Mertonian norm of Universalism, my first thought was of a specific scene in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic Le Petit Prince [The Little Prince].4 The scene is presented in Figure 12.1 .

In this scene, a Turkish astronomer who discovered an asteroid and tried to present the results of his discovery to his peers at an international astronomy conference. However, his peers did not believe his findings because he was dressed in traditional Turkish garb of a fez and a billowing set of shalwar pants. Years later, a Turkish dictator forces his subjects to wear European-style clothing under pain of death. This time, the Turkish astronomer presented his findings at the same conference but with a more European outfit. His peers then immediately believe his findings.

12.2.3 Disinterestedness

When it comes to science, researchers shouldn’t be motivated by commercial pursuits, political interests, or the desire for individual status and prestige. The norm of Disinterestedness is about individual motivations to do science, and that these should be for the sake of science itself. I see this more as Purity of Intention. Merton noted that the norm of Disinterestedness is supported by the fact that scientists are accountable to their peers. If you’re going to do partisan politics under the guise of science, your professional peers are going to point that out, and illustrate how its not science. In essence, your colleagues will largely see through you and understand what you are doing.

This is the most aspirational norm, if you ask me. Consider that in academia hiring and promotion is usually heavily influenced by how many papers you publish or how much grant money you can secure. In fact, the whole purpose of this course is to show how to do ethical programming and statistical analysis, with a number of illustrative cases where this is not the case. Additionally, consider the incentives of funders of research as well, especially private organizations that have their own motives and priority areas. While this norm is not especially realistic, it’s a good thing to strive for, and an important one when it comes to the interpretation of data.

12.2.4 Organized Skepticism

The norm of Organized Skepticism is an institutional and methodological mandate, according to Merton. Basically, for science to work, this has to be part of the process. Science is concerned with a detached scrutiny of beliefs in terms of empirical and other logical criteria. This is related to the process of peer review, in which experts provide critical scrutiny for articles submitted to scientific journals. Merton points to the fact that this norm has often involved questioning the ways things are done, and established beliefs. This can sometimes lead to negative consequences for scientists that question the power assumptions of certain institutions.

12.3 Counter-Norms

Merton’s norms have been quite influential in the sociology of science field, and later work by Mitroff produced a useful list of counter-norms to Merton’s norms.5 These counter-norms are the opposite of Merton’s norms, and nicely capture how science is often conducted in reality. We can refer to them when thinking about the conduct of science as falling on a spectrum with the poles being the norms and counter-norms.

12.3.1 Particularism (in contrast with Universalism)

The idea here is that the acceptance or rejection of a claim depends in large part on the characteristics of who makes the claim. Recall the Turkish astronomer in the Petit Prince example, and how people accepted his claims only after he donned the clothing they deemed to be acceptable. If someone prejudges the claims of scientist from Harvard University as being automatically more credible and valid than those of someone from Jadavpur University in Kolkata, India (where my dad did his Master’s incidentally) without actually seeing their claims, this would be a classic case of Particularism. In fact, they might be implicitly biased against the claimant from Jadavpur University even if they read their study.

Sadly, given what we know about human judgment and how often it relies on quick, mental shortcuts, this counter-norm appears quite realistic. The key then is to design systems of review (such as double-blind peer review) that acknowledge the possibility of Particularism.

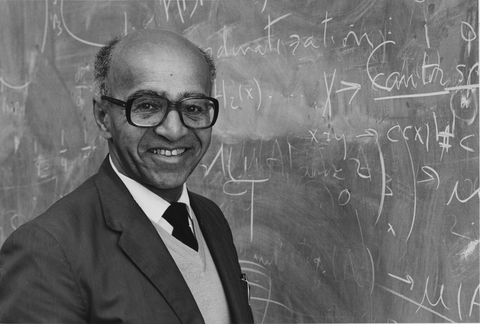

Racial discrimination is a commonly-seen form of Particularism whereby scientists are judged on the basis of their race, rather than on the credulity of their claims. David Blackwell was a very smart man, and made many important contributions to statistics and mathematics including to game theory, probability theory, and Bayesian statistics. He was true luminary in the field, and blazed a trail for others as the first African American elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Blackwell was a postdoc at the Institute of Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton in 1941. Usually, an IAS postdoc would receive a Visiting Fellow appointment at Princeton University, but Blackwell was not afforded this because he was Black. The President of Princeton University was unhappy that IAS had admitted a Black man in the first place.

In 1942, Blackwell had interviewed for a position at UC Berkeley. His PhD advisor Joseph Doob told Jerzy Neyman, the founder of the UC Berkeley Department of Statistics, that among his good students “…Blackwell is the best. But of course he is black. And in spite of the fact that we are in a war that’s advancing the cause of democracy, it may not have spread throughout our own land.”6 This was a pretty spot-on observation by Doob, as Blackwell was not hired at UC Berkeley. The reason? The wife of the department head refused to have a Black man in her house because new faculty members customarily attended dinner at the department head’s house.

Blackwell went on to teach at Howard University for 10 years, and also worked at the RAND corporation. In 1954, Blackwell was hired at UC Berkeley at last, and stayed there for the rest of his long and storied career.

12.3.2 Solitariness (in contrast with Communalism)

Secrecy is the name of the game with this counter-norm. Here, property rights are extended to scientific discoveries. This is actually what one commonly sees when business interests intersect with academic ones. Think about Big Tech companies. They have a strong financial incentive to deliver value to their shareholders through monetizing and protecting their intellectual property. That these are also scientific discoveries illustrates a deviation from the norm of Communalism.

The lines are not always so stark however, and my personal opinion is that there is room for scientific communalism as well as commercial privatization in a number of cases. For example, the founders of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, authored a journal article in 1998 in which they break down their famous PageRank algorithm.7 This provided a valuable contribution to the computer science literature, while also forming the basis of Google Search, which still accounts for just over half of Google’s revenues.8

12.3.3 Interestedness (in contrast with Disinterestedness)

In contrast with Disinterestedness, this counter-norm illustrates the temptation of self-interest and prestige as a chief motivating factor behind scientific discovery. Scientists then work not to for the sake of science, but to secure more funding, more renown, and better positions at more prestigious institutions. This is one of the more realistic counter-norms, in my opinion, as hiring and promotion tend to emphasize a scientist’s output, rather than a dedication to science for the sake of science. The culture of Publish or Perish means that you NEED to be cranking out papers to get a tenure-track position, and certainly to achieve tenure. Consider the implications of this incentive - the system will reward you for papers (be they fraudulent or improperly produced) rather than for producing transparent and robust unpublished work.

This incentive creeps into the academic process in a number of ways. Consider how the prestige of a scientific journal often hinges on how well-cited and influential its articles are, and how this encourages more sensational, novel papers rather than carefully-crafted replications or less sexy, though important, findings. Journals are more likely to publish findings that are statistically significant than findings that are not statistically significant, and this phenomenon is known as Publication Bias.9 This leads to all sorts of distortions of the evidence base which we shall discuss later in the course.

In 2018, a prominent professor of human development, Robert Sternberg, resigned as editor of the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science. His colleagues were not happy that he kept citing himself and publishing in the journal in which he was the Editor. In one of his articles, 10/17 citations (~59%) are his own.10 Other articles had similarly troubling levels of self-citations.11 He was also criticized for publishing several commentaries in the journal without peer review, and with the benefit of garnering multiple citations.

Citing your own work is not a bad thing on its own, but when the majority of your citations are your own, that’s usually a problem! Consider how it may indicate an echo-chamber approach to science, where you are not actually doing the work of reviewing the literature. The case of Robert Sternberg illustrates how once a habit becomes entrenched, it can be very difficult to see the shortcomings and to stop doing it.

12.3.4 Organized Dogmatism (in contrast with Organized Skepticism)

Under this counter-norm, scientists take all the credit for their discoveries, while placing the blame for any inadequacies on previous work by others. Far from doubting their own findings, under Organized Dogmatism scientists promote their own findings with a deep conviction, regardless of what others are saying or doing.

A useful definition of Dogmatism is provided by the late psychologist Milton Rokeach:

A relatively closed cognitive organization of beliefs and disbeliefs about reality, organized around a central set of beliefs about absolute authority which, in turn, provides a framework for patterns of intolerance and qualified tolerance toward others.12

In sum, dogmatism sounds like this “I’m right. I know I’m right. Anyone who says otherwise is wrong.”

Imagine working on a specific area of research for most or all of your career. You become THE leading expert in the topic, and others defer to your authority…for a time. Just as you start to wane in fame, a young hotshot is putting out research that directly critiques your fundamental findings. Will you take an organized skeptical approach and re-assess your work (you should!), or will you instead fight back vociferously and vocally, in spite of mounting evidence against you? While I would love for scientists to be detached enough to scrutinize their own work even if they are the leading expert on it, unfortunately when one’s identity becomes intertwined with their work, it can be quite difficult to be objective.

How do you avoid Organized Dogmatism? Lead with intellectual humility. One excellent example of this is psychologist Julia Rohrer’s Loss of Confidence Project in which she and others admit mistakes that they have made in their previous research. This is a remarkable departure from the tempting counter-norms of Organized Dogmatism and Interestedness, because instead of lauding one’s own accomplishments, it publicly declares instances of one’s errors. Normalizing errors and reporting them is a noble effort, and one that can fight against the counter-norms impeding the progress of science.

As pointed out by Vox science and health editor Brian Resnick,13 there are at least three key challenges to humility (which I paraphrase):

- Our minds (even the geniuses among us) have blindspots and are more imperfect than we are willing to admit.

- We need a culture that celebrates the words “I was wrong.”

- We will never achieve perfect intellectual humility, so we need to be thoughtful with our convictions.

12.4 Conclusion

In short, Mertonian Norms are aspirational and admirable. We should strive to do science in accordance with these norms. However, let’s also be real and recognize that the counter-norms often motivate our behavior. We should be cognizant of them, and engage in habits and practices that actively minimize their influence on our behavior such as transparency and humility, and should strive to enact systems that are consonant with Mertonian Norms such as double-blind peer review, and keeping a lid on self-citations.